A technology transfer strategy based on the dynamics of the generation of intellectual property in Latin-America

Fundación Universitaria Los Libertadores (Colombia)

Received September, 2016

Accepted October, 2017

Abstract

Purpose: Latin American countries have adopted different models of units or transfer offices associated with improved competitiveness; however, it is unclear whether they have been successful or if they have been designed while taking into account the context and particularities of the region. This article aims to summarize the concept of transfer offices and the context of the generation of knowledge through patents in Latin America, and identify strategies that have been suggested in the literature to set up and operate this type of offices, based on the Latin American context.

Design/methodology: Through a systemic literature review, academic articles indexed in the ISI Web of Knowledge and Scopus databases were analyzed to identify the literature related to the context of technology transfer and transfer offices. We cited and analyzed in depth a total of 40 articles. For a review of the Latin American context, 29 documents were reviewed and referenced. Previous documents were taken from specialized networks of the Scientific Information System REDALYC and libraries of universities, such as the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) and the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, among others. Additionally, we added reports and publications by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL), and REDEMPRENDIA. Statistical data provided by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) were used for the analysis of patent generation cases in Latin American countries. Subsequently, the literature of the systematic review was compared with studies by authors and Latin American entities, which give a regional context to this work. Finally, strategies were discussed and identified for the consolidation of transfer offices that impact the generation of knowledge in the region.

Findings: The results of the literature review conducted revealed that several authors have proposed extensive mechanisms for transfer offices in Latin America that reject the general practices based on patent generation, due to the low generation of patents in the region. These mechanisms permit the generation and transfer of knowledge through different means. Therefore, the results of this article allow for a definition of strategies that has been adjusted to the reality and needs of Latin America, in order to consolidate the transfer offices.

Originality/value: The contribution made by this article is focused on identifying possible strategies for consolidating transfer offices that contribute to the technological development of Latin American countries, taking into account the cultural context and limitations of the institutions of higher education.

Keywords: Patents in Latin America, applied research, transfer office models, transfer strategies, university-business relationship

Jel Codes: O31, O32, O33, O34, O38

1. Introduction

The importance of knowledge in modern economies has increased the relevance of university research as a source of innovation, and thus competitiveness (Rojas, 2007; Siegel, Veugelers & Wright, 2007). In this context, higher education institutions have strengthened their technology transfer function as a complement to instruction and research, permitting greater involvement in the productive issues of their economies, boosting the business capacities with their performance and even creating new technology-based companies (spin-offs) (Godin, 2007; OECD, 2010). The relevance of this mission has made it possible to create new organizational models that facilitate the insertion of the higher education institutions in the production environment, thus creating what several agents have referred to as the economy of knowledge (Codner, Baudry & Becerra, 2013).

This article has the following structure, divided into three sections: the first section is a review of the literature, which clarifies the concept and functions of the technology transfer offices and their contextualization in the Latin American environment; the following section reviews the concept of the transfer office model, based on the management of invention patents and their applicability in Latin America; the generation of patents is then reviewed according to patent applications in the different Latin American countries. Finally, a preliminary proposal model is shown for the implementation of Technology Transfer Office (TTO) in Latin America, containing a discussion of strategies for TTOs, followed by conclusions.

This work intends to review the literature on technology transfer offices, focused on the interests and dynamics of the Latin American context. The technology transfer offices are known according to different names, depending on the country or organization; for example, in Argentina they are known as "oficinas de vinculación tecnológica y transferencia (OVTT) (technology association and transfer offices [TATO])"; for the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) the term is "technology transfer offices (TTO)"; and in Spain they are "oficinas de transferencia de resultados de investigación (OTRI)", among other designations. For this work, we will use the initials TTO to signify this type of offices or units in a broad sense.

It should be pointed out that patents will be used as an indicator that reflects, in most cases, the effort made toward research and development by the organizations that apply for them; they are an instrument that promotes interaction between the university and businesses, thus specifying technology transfer processes (Crespi & Dutrénit, 2014; Azagra, Fernández de Lucio & Gutiérrez, 2003).

In spite of the fact that the research found on mechanisms to promote the transfer from higher education institutions to the production sector has a high element of academic production, these mechanisms for promoting transfer products require further research, due to a gap in the literature that analyzes and proposes strategies to consolidate university transfer offices in Latin America, since the lack of strategic guidelines for the higher education institutions context in the region can create ineffectiveness when it comes to fostering innovation (Codner et al., 2013). The revision of strategies is relevant, given that the guides and proposals for the consolidation of the TTO are not entirely adequate when the higher education institutions have a low level of patent generation or production of scientific articles, having ruled out their possible constitution under these circumstances. However, several authors have found that when there are prior interactions with the industry from the higher education institutions, there is a better chance of consolidating a university TTO, even if it is not based on the generation of academic articles or patents (Codner et al., 2013; Ísmodes, 2015; Malizia, Sánchez-Barrioluengo, Lombera & Castro-Martínez, 2013).

Pedraza Amador & Velázquez Castro (2013) stress in their study the need to internationalize the higher education institutions in light of the challenge presented by globalization. Likewise, companies need to improve their competitiveness in foreign markets and to achieve this, they must strengthen their relationships with the academic sector to capture new technological capacities. The higher education institutions should steer their research towards meeting specific needs. In this context, for a TTO to be successful in reaching its transfer objectives, it will be necessary for the higher education institutions to have: suitable academic staff; promotion policies; incentives for researchers; intellectual property management processes and a research orientation (Olaya-Escobar, Berbegal-Mirabent, Alegre & Duarte Velasco, 2017; Siegel et al., 2007).

It is important to keep in mind that the state of technology transfer in Latin America is different from that in developed countries, given the low level of patent generation, although there are already institutional and political structures to promote this activity through the transfer offices (Crespi & Dutrénit, 2014; Ísmodes, 2015).

In the study conducted by Barro Ameneiro (2015) it is evidenced that in Latin America, the countries that report the most activity in patent generation from the higher education institutions are Argentina, Brazil and Mexico; the rest of the countries show less generation in terms of the number of patents. One of the most representative cases is that of Brazil, where the number of patents requested by institutions of higher education is nearly 1,500 applications annually in recent years; in Mexico, it is a little over 500 applications. Argentina, in turn, reports almost 30 patents per year in 2010. By weighting these indicators, comparing them to the population of each country, in 2010, Brazil would have had a little over 8 patents per million inhabitants; Mexico would be above 2 patents per million inhabitants and Argentina would have less than 1 patent, as would the remaining Latin American countries, which did not reach one patent per million inhabitants.

Barro Ameneiro (2015), in his report, shows that the information reported by the higher education institutions evidences an important effort in patent applications nationally, revealing that in the main countries, efforts have been identified through the increase in the average annual growth rates in patent generation during the 2000-2010 period. The country presenting the greatest growth is Mexico (18.3%), followed by Argentina (11.3%). The increase in patent generation from institutions of higher education is accompanied by an increase in specialized human and financial resources, as well as that in terms of the infrastructure required to support technology transfer, such as the TTO-type offices mentioned earlier.

2. Methodology

The present work consists of a systematic review of the literature, in which 40 articles were analyzed in depth from journals indexed in the ISI Web of Knowledge and Scopus databases, to identify the literature related to the technology transfer context and transfer offices, the search being based on the key words: University Technology Transfer; University Patents; University Intellectual Property and their equivalents in Spanish. For the review of the Latin American context, articles were taken from specialized networks of the REDALYC Scientific Information System and libraries from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) and the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. In addition, the reports and publications of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL) and REDEMPRENDIA were also reviewed. For the analysis of patent generation cases in Latin American countries, the statistical data provided by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) were used. In particular, 29 documents with a focus on the Latin American context were reviewed and referenced.

Next, the literature from the systematic review was compared to studies by Latin American authors and organizations, giving a regional context to this work. Finally, the findings were discussed and strategies were identified for the consolidation of transfer offices that impact the generation of knowledge in the region.

3. Review of the literature

3.1. Context of the technology transfer and transfer offices

In the literature, the transfer offices have been identified with two main functions to perform in their work as intermediaries between academic institutions and companies (Codner et al., 2013; Manderieux, 2011; O'Kane, Mangematin, Geoghegan & Fitzgerald, 2015). The first is a function that operates within the academic institution, through the management of the research conducted internally, where its organization and promotion is proposed. This owes to the fact that the academic community does not usually have enough skills and knowledge to provide added value to its research in the production sector (Chapple, Lockett, Siegel & Wright, 2005). The second function is related to the activities outside the academic institution, aimed at preparing the research for use in the business sector. The interrelationship between the university and businesses is important to foster the competitiveness of the latter, as it can be stated that the existence of applied research activities in institutions of higher education that are established in the regions significantly promotes local business innovation (Becker, 2003).

Codner et al. (2013) mention that the transfer offices must identify the research capacity of their institution by taking an inventory of its capacities in order to determine the feasibility of obtaining research results. Furthermore, they should stimulate communication regarding probable inventions and support intellectual property tasks, patent applications and the evaluation of inventions for sale or transfer (Capart & Sandelin, 2004).

Other basic functions of a transfer office are: the evaluation of inventions within the institution of higher education and their possible dissemination; the selection of inventions that must be patented; the search for effective mechanisms of collaboration between internal researchers and external partners that would permit overcoming the barriers associated with interpersonal interactions (Bozeman, Fay & Slade, 2013); the search for interested licensees; the development of marketing plans to promote the outcomes obtained by the higher education institutions; the negotiation of license terms and collaboration agreements and tasks related to the supervision of the licenses granted (Mowery & Sampat, 2005) and providing support for the creation of technology-based companies and the administration of research contracts. These activities make the institutions of higher education, through the TTO, ambidextrous organizations that strive for excellence in research, while at the same time promoting the commercialization of their research results (Ambos, Makela, Birkinshaw & D'Este, 2008; Chang, Yang & Chen, 2009; Huyghe, Knockaert, Wright & Piva, 2014). The capacity to generate ambidextrous organizations is achieved by transcending the limits of the higher education institutions, which makes it possible to create agents that obtain knowledge in a domain and diversify it in order to be applied effectively (Tushman & Scanlan, 1981). Organizational ambidexterity enables efficient models to be created and aligned to meet market demands, while at the same time, being adaptable to changes in the environment (Gibson, Birkinshaw, Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004).

In general terms, it is understood that the main mission of transfer offices is to increase the likelihood that the results of the research conducted by the members of the community of higher education institutions will be consolidated in the form of products and services that are useful to the production sector and thus to society in general (Carlsson & Fridh, 2002). The level of effectiveness of the TTO in positioning the research results depends on the criterion being evaluated; for example, whether the intent is to specify a result transferred to an external body, without defining its real application or if we wish to go as far as to verify the commercial success of the value transferred in the market, or if political interests or the training of human capital are considered (Bozeman, Rimes & Youtie, 2015).

Therefore, through the TTO, the higher education institutions become interfaces between the academic sector and the production sector, creating functions of a business nature (Olaya & Duarte, 2015). This role as an interface is in response to the evolution of modern systems of innovation, as evidenced by the growing need to share knowledge among research organizations and the business sector, reaching both political and economic spheres, backed by states as catalysts of the main actors in a modern system of innovation based on the classic Triple Helix model (Leydesdorff & Etzkowitz, 1996). Also, from the perspective of a business model, the higher education institutions transform it from the perspective of contents, structure and governance, to adapt to new challenges that stem from the interaction with the production sector, where not only the government finances its educational and research activity, rather so does the private sector (Miller, McAdam & McAdam, 2014). According to this model, the consolidation of hybrid organizations is proposed, which has been referred to as the Third-Generation Triple Helix model (TH-III). In this model, there is an overlap among academia, the state and industry, creating hybrid entities, such as the TTO, which serve as an interface among the three actors, where the government provides incentives for these interactions, but does not control them (Olaya, Berbegal-Mirabent & Duarte, 2014).

The hybrid organizations (which serve as intermediary organizations) are part of a trilateral network coordination model that includes the incubators (as a means to promote entrepreneurship), the TTO (for the technology transfer from the higher education institutions to the production sector) and the capital risk companies, among others that may result from said trilateral interaction with the actors involved in the innovation system based on the TH-III model (Leydesdorff & Etzkowitz, 1996).

Figure 1. Triple Helix III model (Leydesdorff & Etzkowitz, 1996)

The TTO, in turn, are described by authors like Huyghe et al. (2014) as organizations that can be set up within the traditional organizational structures of the higher education institutions, under their central governance, which are referred to as traditional TTO, or they can be established in a decentralized manner at the research group or department level, in which case they would be called hybrid TTO. These latter organizations have come to be important structures that generate a major impact on the research results, constituting localized social environments for the promotion of technology transfer (Bercovitz & Feldman, 2008); they eventually evolve into independent organizations that support the processes for the creation of spin-offs (Huyghe et al., 2014). The combination of both types of TTO defined by Huyghe et al. (2014) in the higher education institutions have proven to be an effective means of interrelation, since the hybrid or decentralized TTO is located near the research groups and has the technical knowledge that facilitates the packaging of technology transfer products, generating in turn proximity to the industrial sector that requires the technology that has been developed. In addition, the hybrid TTO communicates easily with the traditional centralized TTO within the higher education institutions, and the latter specializes in the search for financial resources and external advisors as well as in explaining the researchers' needs to the central governance of the higher education institutions (Huyghe et al., 2014).

As can be seen in the previous review, the conceptualization and policies to promote technology transfer processes that have been developed in the world of institutions of higher education, as reported by researchers such as Rogers, Takegami and Yin (2001) and Siegel et al. (2007), are diverse and based on creating economic and political incentives for the higher education institutions from the government or private organizations (Azagra et al., 2003; Bercovitz, Feldman, Feller & Burton, 2001) or the support infrastructure to market the technology (Siegel et al., 2007). There are cases by country that reflect the effects of said strategies, such as the American and Swedish cases, with two different perspectives, where it can be seen how different models of fostering transfer can provide incentives for the generation of knowledge in different ways. In the American case, through economic incentives, technology was transferred to the business world based on systems of intellectual property, and European models like the Swedish one promoted the generation of academic articles and methods of similar dissemination (Carlsson & Fridh, 2002; Goldfarb & Henrekson, 2003). However, the generation of patents in Sweden is high, due in part to the impact of the knowledge generation and network interaction model, which represents an effective model of technology transfer (Skytt-Larsen, 2016).

This is why patents are considered to be a good indicator to measure the technology transfer from the higher education institutions through the TTO, since they provide incentives to obtain economic funds through licensing, research and development subsidies and research contracts (Azagra et al., 2003). Patents usually strengthen the position of inventors in the market and give them time to delve deeper into the development of the new inventions or to develop new applications before their competitors (Hillner, 2014; Teece, Peteraf & Leih, 2016).

3.2 Transfer activities in Latin America

Next, the findings from the literature are reviewed on the state and mechanisms of transfer in institutions of higher education and the production sector in the Latin American context, based on the generation of patents and analytical articles issued specifically for the region. Technology transfer by higher education institutions to the production sector is the topic of extensive debate, given its importance for generating innovation processes in different economies. For several years, efforts have been made to standardize the processes of technology transfer offices according to the model of developed countries, following the example achieved in the United States with the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act (Grimaldi, Kenney, Siegel & Wright, 2011). In this model, the government of the United States allowed the transfer of ownership rights for research conducted with public funds to the institutions of higher education, with very specific exceptions related to national interests. By granting patent ownership to the higher education institutions, it was possible to boost the marketing of the research results to the production sector, giving more freedom to the interaction between these two organizations (Grimaldi et al., 2011; Mowery, Nelson, Sampat & Ziedonis, 2001; Olaya et al., 2014).

It was possible to establish that in most Latin American countries, the governments have defined laws that allow for this same transfer of rights by the state (Malizia et al., 2013; Olaya, Duarte, Berbegal-Mirabent & Simo, 2014; Pontón Silva, Martínez & Hurtado, 2016; Rojas, 2007). However, the impact of this flexibilization has not been as profound as it was in the United States in the 1980s. One of the reasons is that the level of patent generation in Latin America is very low as compared to that commonly seen in the United States and other developed countries (Ísmodes, 2015; Zaldívar-Castro & Oconnor, 2012). This is due to different factors, such as the slow spread of intellectual property (IP) mechanisms in Latin American countries, as compared to developed countries in which the systems of protection date back to the 16th century and the formalization of which stands out, for example, with the creation of the French patent system in 1791 and in the United States, with the creation of the Patent Office in 1836 (Siegel et al., 2007). In developing countries, the intellectual property systems were adopted with the motivation of drawing foreign investments, more than to boost the generation of own knowledge. Therefore, intellectual property rights in developing countries were implemented to "earn a reputation" on an international level and meet the requirements global companies expected in order to invest (Katz & Abarza, 2002; Maloney & Perry, 2005). The result of this situation was that, during the early implementation of intellectual property legislation in Latin America, the effectiveness of these IP systems in developing own knowledge by local citizens was weak, creating a lack of maturity in them (Katz & Abarza, 2002).

Therefore, Latin America forged its technologies with a marked dependence on direct foreign investment and little dependence on R&D. However, contrary to what might be expected, technology transfer is not consolidated through direct foreign investment, due to the relative passivity with which advantage is taken of the technological benefits of said investment (Maloney, 2002; Maloney & Perry, 2005).

Even though the effectiveness to generate knowledge in Latin America has improved thanks to the implementation of suitable legal measures to protect intellectual property and the increase of the capacity of higher education institutions to conduct applied research, the generation of patents by local citizens of these respective countries is still weak (González-Gélvez & Jaime, 2013).

There is a discussion among several researchers regarding the suitability of evaluating the technological development of a country through patents, since many results of research and development are not patented and can be protected by other means, such as industrial secrecy, due to the policies or competitive environment in each country. This article considers that patent generation, even though it is not an absolute indicator, particularly in the case of Latin America, can indicate the capacity to generate innovations in each region and the relevance that the generation of technology has, in addition to being a standardized way of understanding and evaluating innovative proposals around the world (Azagra et al., 2003; Crespi & Dutrénit, 2014; RICYT, 2016). This is thus an interesting source of information that must be taken into account when evaluating technology transfer in Latin American countries.

As analyzed below, patent applications by foreigners currently predominate in Latin America. The next section will briefly review the behavior of patent generation, with an emphasis on the generation among residents and foreigners.

3.2.1 Transfer offices in Latin America

Below is a review of the cases of Argentina, Peru, Mexico and Colombia in the establishment of technology transfer offices and a brief description of their public policies in relation to the TTO.

3.2.1.1 The case of Argentina

In Argentina, the technology transfer organizations originated in the 1980s and in a more institutionalized manner during the 1990s, thanks to the Innovation Development and Promotion Act (No. 23.877/90). Under this law, the figure of the Technology Liaison Unit (TLU) was created as part of the state's modernization policies. It served the function of an interface in order to boost the Argentine innovation system. Later, in a restrictive economic context, this framework promoted the creation of technology transfer capacities on the part of Argentine higher education institutions, within their structures. In a study done by the Department of Science and Technology, it was determined that 45% of the TLUs are associated with an institution of higher education (Codner et al., 2013; Malizia et al., 2013).

In terms of their organizational structure, it was determined that 77% have fewer than 10 people, with an average of 7 people associated with the TLU. 62% are dedicated to professional tasks and 38% to administrative tasks. They are therefore small structures, but with a highly technical nature (Codner et al., 2013).

The mechanisms used to manage the relationship of the TLUs with the production sector were focused on contractual R&D agreements, technical services, consulting, training, and technological marketing, among others. With regard to the financing of the TLU, 43% came from the sale of services and 57% from the university or institutional budget (Codner et al., 2013). In Argentina, there was also a great deal of territorial centralization of the science and technology generation capacities, due to the industrial agglomeration in the same regions, including the Metropolitan, Buenos Aires, East Central and West Central regions, where nearly 80% of the researchers are found (Malizia et al., 2013). Furthermore, it was observed that the creation of companies as spin-offs was very low within the TLU system, as it was identified that only 15% created companies and 62% incubated no companies whatsoever (Codner et al., 2013).

It should be pointed out that Argentina has one of the most inclusive educational systems in terms of access to higher education institutions, since education is free. This means that there are human resources trained for science and technology tasks. There has also been a strengthening of the institution in charge of promoting innovation and technology, the Argentine National Agency for Scientific Promotion and Technology, created in 1997. This agency provides resources and promotes technology transfer processes in the country (Crespi & Dutrénit, 2014; Rikap, 2012). In the case of Argentina, it should be pointed out that a large part of the technology transfer contracts acquired by universities are for consulting and management, which must be considered in the transfer processes (Rikap, 2012).

3.2.1.2 The case of Peru

According to a study conducted by Ísmodes (2015) following a diagnosis of the transfer capacities of the public and private higher education institutions in Peru, three were detected that have formal structures dedicated to the transfer of technology to the production sector. They are Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (UPCH), the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Carlos (UNMSM) and the National Institute of Telecommunications Research and Training (INICTEL-UNI). This same study also found that of the thirteen institutions studied, only three have managed to initiate incubation activities. They are: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (PUCP), UPCH and UNMSM. However, it is mentioned that there are no companies with which they maintain a solid technological base for their operation. It is also mentioned that Peru has clear rules on the protection of intellectual property, which are managed by the National Institute for the Defense of Competition and the Protection of Intellectual Property (INDECOPI) (Ísmodes, 2015). However, in the higher education institutions, there are no clear policies or incentives that promote inventions or patenting. Therefore, in the institutions that engage in research and technology transfer, this transfer is not reflected by a significant generation of patents or spin off companies, rather by services linked to the use of knowledge through advisement, production projects or consulting (Ísmodes, 2015).

According to the survey by the Science and Technology Council of Peru (CONCYTEC) in 2000, only 9% of the companies surveyed in Peru invested in technologies that did not form part of capital goods, and within this group, 61% outsourced all their technology services abroad, 20% had technology licenses and 19% used standardization services and brands (Roca, 2014). The study by Roca (2014) evidenced that Peru did not have a clear public policy on technology and innovation, and so technology is not produced in any significant manner; rather, the country imports most of its technology in a packaged, self-contained or turnkey format, serving as an example for what occurs in most Latin American countries.

The CONCYTEC is the institution that primarily promotes the mechanisms of technology transfer between universities and companies, in which networks of scientific research, information and transfer are created through incentives and economic funds under calls (Marticorena, 2004). Among the priorities established by the CONCYTEC for the development of technologies are the areas of natural resource management and environmental sustainability (Marticorena, 2004).

3.2.1.3 The case of Mexico

In Mexico, the government amended the science and technology law to create Liaison and Knowledge Transfer Units (Unidades de Vinculación y Transferencia de Conocimiento, UVTC). Through these units, the government expected to foster the generation of business projects associated with the production sector. In addition, the accreditation of knowledge transfer offices was promoted as organizations that form part of either institutions of higher education or the private sector, which channel activities of applied research. In this manner, promotion programs were created that attempted to strengthen these structures to promote innovation activities in the Mexican national innovation system (Pedraza Amador & Velázquez Castro, 2013).

In the case of Mexico, the organization that has centralized the promotion of science and technology is the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT). This organization grants stimulus packages and promotes the university-business relationship through different calls for proposals that promote the associations between this type of organizations, granting economic stimulus packages (Calderón-Martínez & García-Quevedo, 2013). In terms of patent generation, it was identified that the main factors explaining university patents in Mexico are determined by the characteristics of the university, such as its size and quality of research, the existence of a TTO and the socioeconomic level of the surrounding area. It is observed that 95% of the university patents correspond to public institutions (Calderón-Martínez & García-Quevedo, 2013).

Specifically, in Mexico, the Science, Technology and Innovation Act of 2009 promoted the creation of knowledge transfer units with the aim of promoting university-business relations. Currently, most Mexican public universities are in the process of transforming the liaison structure to achieve a greater level of interaction with the environment and the production system. However, the creation of transfer offices at Mexican universities is still in its preliminary stages and in some cases it is merely virtual. Of the 80 public universities, 25 have a TTO, created for the most part during the last decade (Calderón-Martínez & García-Quevedo, 2013).

According to the Network of Technology Transfer Offices in Mexico in its 2015 survey, a total of 131 TTO were identified and registered on the network, not including those with branches. Of these, most (with 30 TTO) belonged to private companies or organizations, 12 to public universities, 10 to private universities, 14 to research centers and the rest to technology institutes, government agencies, etc. The average number of employees per TTO in Mexico was 9 people (REDOTT, Red de Oficinas de Transferencia de Tecnología en México, 2015).

Mexico stands out with Brazil for having quickly increased the number of university patents as compared to the rest of the countries in the region. Whereas for the period 1995-1999 only seven Mexican universities had applied for at least one patent, in a more recent period, 2005-2009, this number increased to 15 (WIPO, 2015).

95% of the university patents in Mexico come from public universities, for example, the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), which is the largest public higher education university in the country and concentrates a large part of the patent generation (Calderón-Martínez & García-Quevedo, 2013). In the research by Calderón-Martínez and García-Quevedo (2013), the cases of collaboration between universities and other institutions for the application of patents are still relatively infrequent. Of the 534 academic patents studied during the period 1995-2009, 54 patents were jointly applied for with a university or other organization. Of these 54, 24%, were with a foreign research center, 22% with a Mexican research center, 17% with a foreign company, 20% with a Mexican company, 15% in collaboration with a foreign university and 2% with a Mexican university.

According to Pedraza Amador and Velázquez Castro (2013), based on data from the general directorate of the Institutional Evaluation of the UNAM in 2012, covering the period 1991 to 2009, a total of 748 patents were granted to institutions of higher education, with the main ones being the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), where a large part of the research capacity is centralized, distributed on the Mexican network of public higher education institutions. The UNAM has a well-established technology transfer office that proposes an open innovation model for the promotion of its research results. The Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and the Instituto Politécnico Nacional also stand out.

3.2.1.4 The case of Colombia

According to Jaramillo (2004), the policies linking educational institutions in Colombia to the production sector have been around since the end of the 1990s in most of the top institutions in the country. These policies are more formal and backed by their directive bodies, and they form part of the strategic plan established for the long term. The financial support given by Colombian Department of Science and Technology (COLCIENCIAS) to the higher education institutions to implement projects together with companies through calls for proposals such as the so-called "Co-financing" initiative stimulated the link between both parties, energizing the results that are transferable to the business community (Gómez & Mitchell, 2014; Jaramillo, 2004).

In addition, the constitution and recognition of research groups backed by COLCIENCIAS made it possible to organize the national system of innovation, identifying the capacities specific to each institution. Several educational institutions decided to more extensively offer research groups recognized by COLCIENCIAS as a means of formalizing relations with the productive sector in a way that is more transparent and better organized, creating a more productive and specific interaction by identifying the specific needs and offers between the parties (Gómez & Mitchell, 2014).

Another factor that helped strengthen the business connection with the higher education institutions was the influence of the processes accrediting the quality of the universities by the National Accreditation Council, where the level of association between the university and the business sector is considered in order to earn accreditation. Therefore, being able to demonstrate this interaction with the production sector is favorable to achieve high quality standards from the accrediting organizations, thus providing the incentive for formalizing the technology transfer structures at Colombian educational institutions (Jaramillo, 2004).

Among the first higher education institutions to have transfer offices in Colombia was the Universidad del Valle, which has had organizational structures for the transfer of applied research for the consolidation of innovations in the production sector since 2005. Later, several public and private universities have opted to formalize their liaison structure with the production sector, achieving different levels of impact; however, the generation of intellectual property is still very limited among these institutions (Jaramillo, 2004).

Another initiative that was promoted through COLCIENCIAS is the creation of regional TTOs in 2013 as a model of cooperation among different higher education institutions and associations, promoting regional cohesion. This call to form TTOs resulted in the consolidation of the following organizations in the different territorial areas (Jaramillo, 2004).

-

•Atlantic TTO (with participation by higher education institutions, research centers and several companies).

-

•Eastern Strategic TTO, with headquarters in Bucaramanga.

-

•Tecnnova TTO (with participation by universities in Antioquia, among others).

-

•Universidad Distrital TTO (in association with the Department of Development of Bogotá).

-

•Connect Bogotá TTO (with participation by Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Universidad de los Andes, Universidad Nacional de Colombia and Universidad de la Sabana and companies like Corona, the Grupo Bolivar and Sura, among others).

-

•Colombian Ministry of Defense TTO (with participation by the Colombian Air Force and several scientific allies, such as Colombia's largest oil company (ECOPETROL).

This composition of TTO organizations permits the cohesion of different institutions with similar characteristics to strengthen technology transfer. However, to date, there has still not been a clear result of their impact on business competitiveness.

With regard to aspects of intellectual property, in the study conducted by Jaramillo (2004), it was established that most Colombian higher education universities have only very recently defined policies regarding intellectual property, which were developed as the result of great internal discussion. Accordingly, some policies have been defined with a legal and statutory basis approved by the top administrators of the institutions of higher education, but to date, their applicability and clarity is still weak, which can hamper the multiplication of successful relations between the universities and the business world.

As a result, it is generally the legal offices of the higher education universities that are in charge of matters of intellectual property, and awareness has still not been created among the researchers themselves regarding their importance and relevance in terms of research results. It is possible that this situation has propitiated the few cases of negotiation of technology or knowledge licensing reported in the literature (Bitran, Benavente & Maggi, 2011; Gómez & Mitchell, 2014).

For the specific case of Colombia, in the study conducted by González-Gélvez and Jaime (2013) on patenting in higher education universities in Colombia, the low level of patent generation is evident in the country. The study shows that the first patent application from a Colombian university was identified in 1988, and from this date until 2010, a total of 69 unique patent applications were detected. The most active university was the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, followed by the Universidad del Valle (López, Schmal Simón, Cabrales & García, 2009).

The same study by González-Gélvez and Jaime (2013) revealed that utility model patent requests, which are less demanding than those at the invention level, have very low application rates and approximately 40% of these applications have been abandoned by the applicants. This evidences that there is still a lack of maturity in the Colombian intellectual property system, which is weak in terms of patent generation and their granting.

From the different studies conducted on the case of Colombia, it is evident that there is a practically generalized lack of culture regarding the topics of intellectual property among researchers at Colombian higher education universities, who still do not know about the necessary concepts regarding patents, industrial designs and industrial secrets that could promote the results of their research. This produces the low level of generation of patents and other mechanisms of intellectual protection that still prevails in Colombian higher education universities (González-Gélvez & Jaime, 2013; Olaya et al., 2014).

Figure 2. Patent applications for inventions presented to the SIC between 1988 and 2010, according to the applicant university in Colombia (González-Gélvez & Jaime, 2013)

3.3 Levels of formalization of technology transfer activities in Latin America

Different studies on technology transfer skills and TTOs in Latin America point to the increase in the formalization of research and development policies, which denotes a generalized increase in the level and scope of the university entities in Latin America. Therefore, the institutions have managed to formalize in their regulations the way to interact with and provide incentives for applied research (Barro Ameneiro, 2015).

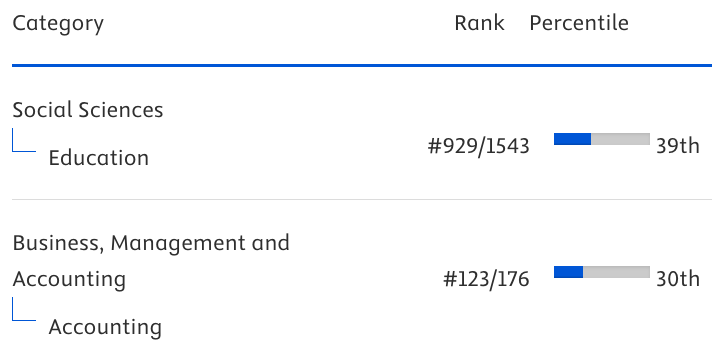

One way to have a vision of the infrastructure present in the higher education institutions for technology transfer is to evaluate the percentage of organizations according to the country average that have a TTO, business incubator or technology park.

As can be seen from Table 1, more than 50% of the educational institutions in the largest countries in Latin America have TTOs and business incubators, while scientific parks are the rarest infrastructure in the region.

% of Universities |

Transfer offices |

Incubators |

Scientific parks |

> 75% |

Mexico |

- |

- |

51% - 75% |

- |

Mexico |

- |

25% - 50% |

Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Uruguay |

Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Uruguay |

- |

<25% |

Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, Bolivia, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Venezuela |

Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, Bolivia, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Venezuela |

Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Cuba, Ecuador, Panama, Uruguay, Bolivia, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay |

No data |

- |

Honduras, El Salvador |

Costa Rica, Peru, Guatemala |

Table 1. Classification by country, according to the percentage of higher education universities that have a TTO, incubator or technology park (Barro Ameneiro, 2015)

Table 2 shows that most of the higher education universities in the largest Latin American countries have regulations on intellectual property, with a smaller proportion of regulations on licensing. This could be due to the fact that topics regarding intellectual property are defined as an initial case to be regulated and, it is not relevant to regulate licensing processes in all cases, due to the low patent generation.

To identify the levels of formalization of the TTOs, it is common practice to examine the educational institution's guidelines for technology transfer with the production environment (Cruz Novoa, 2014). The research conducted by the Emprendia Network, which studied 17 Ibero-American higher education universities, defined the level of regulation of research, development and innovation activities at the higher education universities studied in Ibero-America as a variable for the analysis of these activities. Cruz Novoa (2014) demonstrated that regulation is focused on four pillars: regulation of intellectual property, R&D licensing, the creation of spin-off companies and the resolution of conflicts of interest. These pillars were evaluated through surveys of the higher education universities belonging to the Emprendia Network, with the results shown in Table 3.

% of Universities |

Intellectual property |

Licensing of research results |

Creation of spin-offs |

51% - 75% |

Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico- |

- |

- |

25% - 50% |

Ecuador, Uruguay |

Brazil, Mexico |

Colombia |

<25% |

Costa Rica, Cuba, Panama, Peru, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Venezuela |

Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Guatemala, El Salvador, Venezuela |

Brazil, Mexico, Costa Rica, Panama, Peru, Guatemala, Venezuela |

No data |

Bolivia |

Cuba, Ecuador, Peru, Uruguay, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Paraguay |

Cuba, Ecuador, Uruguay, Bolivia, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Paraguay |

Table 2. Classification by country of percentages of higher education universities with intellectual property, licensing and spin-off regulations (Barro Ameneiro, 2015)

Regulations |

Number of higher education universities |

% of higher education universities |

Intellectual property |

14 |

82,00 % |

Licensing of R&D results |

10 |

59,00 % |

Formation of spin-off companies |

10 |

59,00 % |

Resolution of conflicts of interest |

1 |

6,00 % |

Table 3. Existence of regulations governing R&D activities in Ibero-America (Cruz Novoa, 2014)

The results show that there is a greater presence of intellectual property regulations and, to a lesser extent, regulations governing licensing and spin-off formation. However, the study identified that of the 17 higher education universities studied, each had a technology transfer office, and in spite of their age, a noticeable difference was evidenced from one to another (Cruz Novoa, 2014).

3.4 Generation of patents in Latin America

Next, the generation of patents in different Latin American countries is reviewed, starting with the Colombian case. Countries with a similar volume of patents generated per year are grouped together in order to adequately appreciate their differences. Accordingly, Argentina, Chile and Colombia, with a volume of less than 5,000 patents per year, are compared altogether in the first group. Mexico and Brazil are grouped together as countries with a larger number of patents generated per year, which amount to a volume of less than 25,000 patents. The rest of the Latin American countries, including Bolivia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay are grouped together based on their low level of patent generation, which do not exceed 5,000 patents per year altogether.

In Colombia in 2014, according to the report by the WIPO (2015), patent applications amounted to 1,898 by foreigners and only 260 patents were applied for by Colombian inventors (See Figure 3).

This scenario is repeated in practically all Latin American countries, according to the report by the WIPO (2015), which shows that an important gap is maintained between patent applications by residents and non-residents. This comparison of patent generation is important, as it indicates that a large part of the technological developments protected in Latin American countries are not patented internally by residents, rather most are brought by foreigners through multinational companies that develop technologies in their countries of origin and simply protect their inventions in Latin American markets through international treaties (Crespi & Dutrénit, 2014; Roca, 2014).

Figure 3. Patent applications in Colombia (WIPO, 2015)

3.4.1. Resident/non-resident patent applications in Argentina, Chile and Colombia

As seen in Figure 4, the number of patents applied for by foreigners in this group of countries (Argentina, Chile and Colombia) represents the highest numbers, as shown by the top lines, while the number of patents requested by residents is represented by the three lower lines, demonstrating a large gap between the two groups.

Figure 4. Residents vs. non-resident patent applications in Argentina, Chile and Colombia (WIPO, 2015)

3.4.2 Patent applications by residents/non-residents in Brazil and Mexico

Figure 5 shows a very similar scenario for Brazil and Mexico, where the number of patent applications from foreigners is far greater than those applied for by residents, as shown in the same Figure. Brazil has the largest number of patents requested by non-residents in Latin America. The number of patent applications from residents in Latin America has remained at a relatively constant number, as can be seen in the two figures shown above.

Table 4 shows the number of patents in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico between 2007 and 2014, tabulated for residents and non-residents.

Figure 6 shows the total patent applications for the five countries studied (Argentina, Mexico, Brazil, Colombia and Chile). According to these data, more than 85% of the patent applications in the region between 2007 and 2014 were submitted by foreigners.

Figure 7 shows the total patent applications for Bolivia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay, where the same trend and gap is observed between resident and non-resident patents, which is even more pronounced in this case, reaching levels at which nearly 95% of the patents are applied for by foreigners. The PCT (Patent Cooperation Treaty) international patent cooperation system is limited and underutilized in Latin America by its residents, due to the low number of patent applications. Only Brazil stands out for having the highest number of patents applied for through the PCT in Latin America, with 548 for 2015, followed by Mexico, with 317 (WIPO, 2015). In the case of Colombia, the Patent Office of the Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio (SIC) reported a total of 14 patent applications through the PCT system by residents in 2014.

Figure 5. Residents vs. non-resident patent applications in Brazil and Mexico (WIPO, 2015)

Country |

Origin |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

Argentina |

Resident |

937 |

801 |

640 |

552 |

688 |

735 |

643 |

509 |

Argentina |

Non-Resident |

4.806 |

4.781 |

4.336 |

4.165 |

4.133 |

4.078 |

4.129 |

4.173 |

Brazil |

Resident |

4.194 |

4.280 |

4.271 |

4.228 |

4.695 |

4.798 |

4.959 |

4.659 |

Brazil |

Non-Resident |

17.469 |

18.890 |

18.135 |

20.771 |

23.954 |

25.637 |

25.925 |

25.683 |

Chile |

Resident |

403 |

531 |

343 |

328 |

339 |

336 |

340 |

452 |

Chile |

Non-Resident |

3.403 |

3.421 |

1.374 |

748 |

2.453 |

2.683 |

2.732 |

2.653 |

Colombia |

Resident |

128 |

126 |

128 |

133 |

183 |

213 |

251 |

260 |

Colombia |

Non-Resident |

1.862 |

1.818 |

1.551 |

1.739 |

1.770 |

1.848 |

1.781 |

1.898 |

Mexico |

Resident |

629 |

685 |

822 |

951 |

1.065 |

1.294 |

1.210 |

1.246 |

Mexico |

Non-Resident |

15.970 |

15.896 |

13.459 |

13.625 |

12.990 |

14.020 |

14.234 |

14.889 |

Table 4. Number of patents for residents and non-residents, by country 2007-2014 (WIPO, 2015)

Figure 6. Patent applications by residents and non-residents in Argentina, Mexico, Brazil, Colombia and Chile (WIPO 2015)

Figure 7. Patent applications by residents and non-residents for Bolivia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay (WIPO 2015)

3.4.3 Patent applications through PCT in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico

Figure 8 shows the total number of patent applications through the PCT in the aforementioned countries, without breaking them down by residents or non-residents. Although important growth is observed over the years 2007-2014 in this group of countries, Mexico is the country that shows the highest rate of growth since 2012.

Figure 8. Patent applications through the PCT treaty for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico (WIPO 2015)

This behavior owes in part to the ease of patent registration by foreigners within the international PCT treaty; however, it is clear that due to the low level of patentable research results by Latin American citizens, there are more foreigners who register their inventions than local citizens. Many foreign companies with commercial interests in these countries use the schemes from the PCT treaty to protect their technologies at the same time in several Latin American countries. Likewise, the low generation of local technological capacities is the basis for such a pronounced deficit in patent applications (Maloney & Perry, 2005).

In this scenario, this article proposes the hypothesis that questions whether the model of transfer offices based on the generation of patents and their licensing is appropriate for Latin America or whether new strategies should be considered for the transfer of knowledge and technology from the higher education universities to obtain greater development of the economies based on university-based innovation, technological development and research (Barro Ameneiro, 2015; Katz & Abarza, 2002; Zaldívar-Castro & Oconnor, 2012).

4. Discussion

The role of transfer offices in the Latin American context has demonstrated important advances in terms of the structuring of this type of offices, where it has been evidenced that the most representative higher education universities have offices of this type. However, it has been shown that most of these offices perform tasks of advisement or consultancy for the business sector, but they are still weak in their technology licensing activities, due to the scarce use of the means of intellectual property, such as patents or industrial secrets (Barro Ameneiro, 2015; Bitran et al., 2011; Maloney & Perry, 2005).

In the case of the United States, the implementation of the Bayh Dole Act in 1980, where the government transferred its intellectual property rights to the higher education universities or organizations that had received state financing, made it possible to promote the commercialization of research results in a decisive manner, positioning this country as one of the centers of technological generation in the world (López et al., 2009). Authors such as Siegel et al. (2007), in their studies on the impact of the Bayh Dole Act, demonstrate that after this law was passed, there was a substantial increase in the creation of technology transfer offices in the United States, permitting an increase in the number of patents granted to higher education universities and companies, in addition to a larger volume and value of R&D contracts with companies. Authors such as Mowery et al. (2001) also demonstrate an increase in investments in marketing and organizational models within universities, created specifically to promote the generation of patents, as an effect of the implementation of this law.

The Latin American case is different, due to the focus centered on education that the higher education universities have had throughout their history, with a low level of interest in applied research. The research capacities have only recently been promoted, so the magnitude of applied research is still limited. The decision of Latin American governments to transfer their rights as was done under the Bayh Dole Act was a mechanism of imitation, which did not substantially impact the generation of patents in the region, as can be observed from the different patent generation results (Katz & Abarza, 2002; WIPO, 2015).

The proposal for the creation of patent management models based on Latin American cases, such as that defined by López et al. (2009) is interesting and must be considered, especially with regard to the initial processes for evaluating ideas and projects with probabilities of obtaining intellectual protection on the part of university researchers. López et al. (2009) propose evaluating ideas based on capacities to identify technological information, technological surveillance and technical advisement in the specific definition of technologies, among others. The following processes proposed by this same author, such as the possibility of having sponsors or partners, are activities typical of a TTO in order to achieve good patent management. Also within this process, the definition of commitments and responsibilities through contracts with researchers and interested external agencies will be vital to achieve the applied research results, as proposed by this author. In the last stages of his model, the exploitation of patents through licensing forms part of the good management of intellectual property of the higher education universities. However, the implementation of a model such as that defined by López et al. (2009) is not enough when the institutions do not have an organizational culture focused on the generation of research ideas and the support and incentives to implement them are very scarce (Friedman & Silberman, 2003), as is commonplace in the Latin American context.

This situation reconsiders the appropriateness of setting up technology transfer offices, following the model of developed countries, supported by the licensing of intellectual property, based on more consolidated research structures that seek, among other things, the generation of patents in order to have a strong and dynamic position and transfer knowledge to the production sector. Due to the scarce presence of TTOs in Latin America with this model focused on intellectual property (patent generation), it becomes interesting to reconsider the concept of TTOs in terms of the needs of each region, transforming its role as an instrument of interface, aimed at the production environment where it operates. In addition, the design of research activities should be considered so that over the long run, these offices can become units with the potential to manage intellectual property in a more active fashion, increasing the likelihood that the research results will be appropriated, as suggested by Codner et al. (2013) and Ísmodes (2015).

According to the guide from the World Intellectual Property Organization (Manderieux, 2011) for the creation of transfer offices, it is important to have transferable, marketable products or to have a high level of scientific production evidenced by publications in high impact journals. This can be a relevant starting point to determine the appropriateness of implementing technology transfer offices in university organizations, but it is not the only one.

It is worthwhile to stress the identification of the skills of researchers, which along with a culture of generating ideas and research projects, permit the transfer of results to the production sector, although still without the deliberate intention of being the subject of patents or intellectual property, but rather as research contracts or incentives for the results obtained with companies, as well as the creation of spin-offs (Huyghe et al., 2014).

Along the same lines, the Spanish case can be taken as an example of generating transferable products that are not susceptible to being patented. This country has reached income levels nearing those of developed countries, in spite of having low levels of investment in R&D. It was observed how with the commitment to organizational innovations and production management, Spain managed to improve its competitive position and better link the business sector to the universities, in order to create solutions according to those commitments, even though this does not lead to an increase in direct economic income through licenses for the technology transfer offices (Caldera & Debande, 2010; Caselli & Tenreyro, 2013).

In Latin America, there are many technological developments from higher education universities that have already been adapted to their context, but they do not have the level of novelty necessary to be patentable. However, they can be applied to production programs with a social impact, for example, in isolated or rural communities, but due to the lack of a culture of innovation and transfer, these solutions are still not used in these areas due to the absence of channels of communication and transfer that permit their use and financing.

Therefore, the WIPO model (Manderieux, 2011) described in Figure 9 to determine the feasibility of a TTO that emphasizes the need to have a high level of scientific production or tangible, transferable products, must stress the possibility of creating technology transfer units for the Latin American context in which the application of policies appropriate for each university organization, based on the diagnosis of the skills of its researchers, would allow for the consolidation of an organizational culture focused on the generation of ideas and projects that are transferable to the production sector. All of this is for the generation of patents that are intended to consolidate the TTO over the medium to long term.

In addition, the generation of articles should not be a decisive factor for defining the transfer capacities, as it has become apparent how the spin-offs tend to be more effective mechanisms for this type of transfer. There are also other means of transfer, such as personal meetings and cooperative R&D agreements, among others (O'Shea, Allen, Chevalier & Roche, 2005; Rogers et al., 2001).

The conceptualization of the importance of intellectual property by university researchers is relevant to achieve advances in the generation of patents over the long term in the higher education universities, since lacking the capacity to generate ideas with the level of novelty to be patented, it is necessary for researchers to be familiar with their concepts and requirements, in order to understand how close they are to being patentable inventions. Knowledge is also required about intellectual property to prevent missed opportunities for patenting that have been identified in the different Latin American higher education universities, as documented by the Universidad Nacional de Quilmes in 2012, in the study by Codner et al. (2013). This study reported how some scientific articles published by their researchers are referenced on patent applications in the United States and Europe, and in some cases, these have been a fundamental part of the invention awarded, but the authors of the article were unaware of said patent application. Accordingly, it was demonstrated that the research results of some Latin American higher education universities have the potential for industrial application, but due to the lack of knowledge on the possibility of patenting them, the opportunity is missed, which is then taken advantage of by third parties who have access to these articles, resulting in what the author refers to as a blind technology transfer (Codner et al., 2013).

Figure 9. Model to determine the feasibility of a university TTO (Manderieux, 2011)

In the report by the CEPAL proposed by Katz and Abarza (2002), it is mentioned how large multinational companies are increasingly more attentive to this type of opportunities that can be patented, thanks to the poor protection management that Latin American researchers receive. For this reason, the multilateral organization suggests that public policies be established to boost knowledge and opportunities for intellectual property and for an intellectual inventory to be done on the potential for protection in all areas, particularly in bio-genetics and cultural areas where there are potential opportunities based on the native characteristics of the Latin American regions, their botanical, agricultural and dietary wealth, among other areas, in order to achieve higher levels of protection for them and market these products more energetically on international markets.

History has shown that it is possible to transform emerging economies, such as in the case of Korea, which in spite of its peculiarities, is interesting to highlight. In the 1960s and 1970s, South Korea generated a smaller number of patents than Latin America. However, since the 1980s, the trend has reversed noticeably, to the point that today Korea generates 15 times more patents than those awarded to all the residents of Latin America together, according to figures by the WIPO. Korean residents in 2014 generated 164,073 patent applications (Bravo-Ortega & García Marin, 2007; WIPO, 2015).

This level of generation of intellectual property makes this country a power in technology generation. A large part of this achievement, while in part the product of commercial protectionism, is based by the commitment of higher education universities to technological development and innovation applied to industries that today form large conglomerates that are very competitive, not only in South Korea, but around the world (Bravo-Ortega & García Marin, 2007).

4.1 Strategies for consolidating TTOs in Latin America

Due to the environment and underlying conditions in Latin America, where there are many countries with capacities in research and development that are underutilized to a large extent by the cultural environment, as the result of a lack of incentives and structures appropriate for the promotion of academic results for use in production, as well as the lack of capacity for autonomous learning (Maloney, 2002), it is necessary to consider different strategies that suggest a path for the consolidation of a model of technology transfer offices that is appropriate for the Latin American environment.

According to several Ibero-American authors, for a TTO to be able to generate relevant impacts in terms of technology transfer mechanisms, aspects such as their university policies on technology transfer must be taken into account, as well as specialized structures for technology transfer intermediaries and the institutional characteristics of the university, such as its size, the level of qualification of its staff and the quality of its level of research (Caldera & Debande, 2010).

The definition of an appropriate institutional policy within the academic environment is necessary to take advantage of the capacities of the Latin American academic institutions, since it has been determined that several countries have institutions with good research capacities, but they have not yet managed to consolidate their research results in production projects or the more effective generation of patents. Therefore, a regulatory framework is proposed that should be created (or modified, if one already exists) by each institution to promote their research results with the following characteristics (Rojas, 2007):

-

•Defining statutes and internal rules in which it is stated that the institutional mission of the institution of higher education is ingrained in its research work for the production sector. This must be clear from the definition of objectives for generating new knowledge.

-

•Promoting policies of dissemination and confidentiality that permit generating a balance to appropriate and protect useful research results for use in the production sector.

-

•Reviewing the concordance of said policies and research objectives with the national legislation in each country to strengthen a good interrelationship with commercial policies and the promotion of innovation.

-

•Establishing a scheme for regulation and contract clauses for the financing of research or projects in conjunction with the business sector.

In addition to defining clear policies and incentives within the university institutions to promote technology transfer (Blomström & Sjöholm, 1999; Olaya-Escobar et al., 2017), the inclusion of the higher education universities in knowledge networks or clusters and think tanks is key to increasing productivity and the possibilities for new products to be transferred (Park, Ryu & Gibson, 2010). For example, it is mentioned that one of the most important strategic assets for the competitive development of the Swedish forestry industry has been the knowledge networks that permit technology to be transferred to the sector (Goldfarb & Henrekson, 2003). These networks and clusters that make it possible to identify technological development opportunities are responsible for jumps over to other technologies, as in the case of Nokia, which left the forestry industry to become a leader in the telecommunications sector (Maloney & Perry, 2005).

It is important to note that the transfer offices must create high levels of legitimacy to interact in these knowledge networks and to remain and be useful within their academic environment. To create legitimacy, they face a great challenge to balance the demands and interests of their academic environment within the university institution, where different departments and governance units exist, whose interests are sometimes contradictory (Navis & Glynn, 2011), and the demands that come from the expectations of the production sector (O'Kane et al., 2015).

The need to create legitimacy must be aligned with the organizational culture of the institutions of higher education in Latin America, with the elimination of the need in many cases for technology transfer based on intellectual property, in favor of multi-faceted mechanisms for the exchange of knowledge, such as academic articles, reports, information exchanges through informal means, conferences, recently contracted university studies and research contracts or cooperation agreements, among other forms of knowledge exchange, which form part of the new paradigm of open innovation (Miller et al., 2014; Perkmann & Walsh, 2007). As a matter of fact, open innovation in university-business transfer processes is backed for the most part by highly evolved relational means, in other words, through association or research agreements that permit the parties to interact, unlike traditional means, such as the transfer through the licensing of intellectual property, which is generated in practically one single direction, without creating any substantial exchange or collaboration (Perkmann & Walsh, 2007).

5. Conclusions

In the case of Latin America, the configuration of strategies and fields of action to define and operate transfer offices is important to transform the situation of technological dependency experienced by the region. The discussion on the configurations, strategies and fields of action of technology transfer offices is increasingly more necessary in the Latin American context in order to find mechanisms that permit integrating elements to energize the technological development in the production sector into the culture, based on the regions own natural resources, industrial resources and cultural wealth.

The main objective of this article is to contextualize the environment of technological production in the Latin American countries from the perspective of patent generation. Having observed the low level of patent generation by higher education universities in Latin America and the context of patentability, where outside companies (which have their origins outside the country, such as multinational corporations with headquarters in a developed country) are the ones that dominate in terms of intellectual property, thanks to international treaties (free trade treaties or the cooperation treaty in the area of patents, PCT), the authors suggest that following the model of technology transfer offices in developed countries is not the most appropriate. A model must be found that adapts to the culture and peculiarities of the Latin American region.

Therefore, to diagnose the technological capacities and develop ideas and projects with potential, appropriate models must be created by the institutions of higher education based on unexplored capacities in inconclusive projects or indications from prior consulting work or those with the probability for agreements, so that a base is founded that permits the development of transferable technologies, both to the traditional industrial sector and production sectors that impact the social development of vulnerable communities in Latin American countries.

By reviewing the academic and business literature, it is evident that the result of the technology transfer objectives in Latin America has not been satisfactory for the consolidation of a mature technological base, due to historical events that have led to the technological dependence in the region (Crespi & Dutrénit, 2014). Latin America has belatedly attempted to replicate technology development policies from developed countries, which has proven ineffective for its socioeconomic context and has not managed to achieve a true social contract with science and technology (Guston, 2000).

This study recommends delving deeper into research and documentation of specific cases in institutions of higher education that can offer learning opportunities for defining policies on both a macro level, from the perspective of the national government, and on the micro level, in the higher education universities, in order to increase the technology transfer mechanisms. Additional research is therefore required on the topic in order to define models and methodologies to promote technology transfer from higher education universities. Models applicable to higher education universities that have a greater level of patent generation, such as at some public universities in the most representative countries of the region, must also be suggested to determine whether it is possible to increase the level of patent generation with the implementation of strategies such as those mentioned in this document. The strategy for consolidating the TTO may vary, depending on the area of knowledge emphasized by the institution, so it would be of interest to examine these divergences.

The limitations of this article center on the fact that it reviews only the Latin American context, and so expanding its scope to more countries, such as the Ibero-American case, would be interesting for future research proposals. The search was also limited to specialized databases and sector reports, so the spectrum of information to be analyzed could also be extended.

The creation of research capacities is necessary to increase the possibilities of transfer from university institutions, which must be reviewed in future research associated with a business character that results in greater innovation and reduced technological dependence, which is evident in practically all Latin American countries. This can be achieved by promoting research on native natural resources, supported by biotechnology or in areas of medicine that consider the idiosyncrasy of the population or in many other areas with potential for leadership in innovation.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received financial support for the research and publication from Fundación Universitaria Los Libertadores.

References

Ambos, T., Makela, K., Birkinshaw, J., & D'Este, P. (2008). When Does University Research Get Commercialized? Creating Ambidexterity in Research Institutions. Journal of Management Studies, 45(Dec), 1424-1447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00804.x

Azagra, J. M., Fernández de Lucio, I., & Gutiérrez, A. (2003). University patents: Output and input indicators... of what? Research Evaluation, 12(1), 5-16. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154403781776744

Barro Ameneiro, S. (2015). La Transferencia de I+D, la Innovación y el Emprendimiento en las Universidades. Educación Superior en Iberoamérica. Informe 2015. Centro Interuniversitario de Desarrollo - CINDA Red Emprendia Universia, 541.

Becker, W. (2003). Evaluation of the Role of Universities in the Innovation Process. Volkswirtschaftliche Diskussionsreihe, (241), 28.