Intellectual capital and relational capital: The role of sustainability in developing corporate reputation

Patricia Martínez García de Leaniz, Ignacio Rodríguez del Bosque

Universidad de Cantabria (Spain)

Received: November 2012

Accepted: February 2013

MARTINEZ GARCÍA DE LEANIZ, P.; RODRÍGUEZ DEL BOSQUE, I. (2013). Intellectual capital and relational capital: The role of sustainability in developing corporate reputation. Intangible Capital, 9(1): 262-280. http://dx.doi.org/10.3926/ic.378

------------------------

Abstract

Purpose: Intellectual capital offers a potential source of sustainable competitive advantage and is believed to be the source from which economic growth may sprout. However, not many papers analyze the effect of sustainability in the elements involving intellectual capital. This paper seeks to highlight the key role played by corporate sustainability on corporate reputation as one of the key components of relational capital based on the knowledge-based theory. In order to fulfill this objective we consider economic, social and environmental dimensions of corporate sustainability.

Design/methodology/approach: Authors develop a structural equation model to test the hypothesis. The study was tested using data collected from a sample of 400 Spanish consumers.

Findings: The structural equation model shows that sustainability plays a vital role as antecedent of corporate reputation and relational capital. Findings suggest that economic, social and environmental domains of sustainability have a positive direct effect on corporate reputation. Additionally, this study shows that economic sustainability is considered to be the most important dimension to enhance corporate reputation.

Research limitations/implications: Relational capital involves several dimensions which have not been incorporated to this study. Thus, future studies may analyze the role of corporate reputation and sustainability in the formation and development of the different relationships that conform relational capital. Finally, the complicated economic environment currently experienced worldwide may affect the perceptions of Spanish consumers and their ratings. The crosscutting nature of this research inhibits an understanding of the variations in the perceptions of the customers surveyed over time, suggesting that this research could be expanded by a longitudinal study. Secondly, the current study has been conducted with consumers of hotel companies in Spain and it is not clear in how far the findings can be generalized to other industries, stakeholders or countries.

Practical implications: This research allows managers to identify the activities in which companies can devote resources to in order to increase firm's reputation. By knowing these specific economic, social and environmental activities, companies can understand, analyze and make decisions in a better way about its sector and about the stakeholders that assess these initiatives.

Originality/value: To our knowledge, in any case it has been studied simultaneously the influence of sustainability dimensions on corporate reputation, which is a knowledge gap in the academic literature.

Keywords: Intellectual capital, relational capital, sustainability, corporate reputation

JEL Codes: M00, M10, Q56

------------------------

Introduction

The justification of firm success has suffered an important change during the last years. A key responsibility has been given to endogenous and firm-specific factors in order to explain sustained generation of wealth and economic growth in organizations (Barney, 1986, 2001; Dierickx & Cool, 1989; Grant, 1991). Practitioners and scholars have highlighted the strategic relevance of intangible resources in rent generation. Intangible assets are primarily based on information and knowledge, so that, this assets are difficult to detect, imitate, replicate and to transfer in the markets (Martín de Castro, López & Navas, 2004). These characteristics explain the increasing attention about studying this kind of phenomena in the academic literature. The interest in the role that knowledge plays within organizations has developed one main research stream known as intellectual capital (Bueno, 2000). This mainstream has been named by other scholars as the knowledge-based view or as the knowledge-based theory of the firm (Grant, 1996; Spender, 1996; Martín de Castro et al., 2004).

This paper can be considered as part of these research streams and shows a model about the relation between sustainability dimensions and corporate reputation, as one of the main components of relational capital, since the current academic literature does not have an understanding of how these notions interact in the context of the knowledge-based theory of the firm. Previous studies argued that intellectual capital has positive influence upon competitive advantages of firms (Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Martín de Castro et al., 2004; Hormiga, Batista & Sánchez, 2011). However, as stated by Chen (2008) “no research explored whether intellectual capital about sustainability issues has a positive effect on competitive advantages of firms”. Companies engaging in sustainability (e.g. environmental management, green innovation…) actively can not only increase productivity, but also improve corporate images and thereby obtain corporate competitive advantages under the trends of popular sustainability consciousness of consumers and severe international regulations (Chen, Lai & Wen, 2006). Although previous scholars had paid great attention to explore intellectual capital, none explored intellectual capital about sustainable aspects (Chen, 2008; Figge & Hahn, 2005). Therefore, this study wanted to fill this research gap by exploring the relation between sustainability dimensions and corporate reputation as one of the main components of relational capital. In this proposal three issues must be highlighted: (1) relational capital, (2) corporate reputation and (3) sustainability.

Relational capital is based on the idea that firms are considered not to be isolated systems but as systems that are, to a great extent, dependent on their relations with their environment (Hormiga et al., 2011) and it can be structured into different levels. Based on the model for the measurement and management of intellectual capital “Intellectus Model” (CIC, 2012), the first level refers to knowledge and its management regarding the relations that organizations can maintain with the agents that are part of its closer environment. This nearer environment usually presents several agents such as customers, suppliers or shareholders, among others. The capacity of the firm to understand, analyze and make decisions about its industry depends on the study of the relations previously mentioned, that can be considered as a direct influence over the firm's possibilities to achieve rents.

On the other hand, corporate reputation is considered as a moderating element for inter-organizational relations (Martín de Castro et al., 2004). This way, corporate reputation is understood as the “set of perceptions held by people inside and outside a company” (Fombrun, 1996). This notion, as the awareness or perception about corporate behavior by its stakeholders (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990; Fombrun, 1996), will influence relational processes with the agents of the closer environment.

Finally, most academics and practitioners claim that how executives respond to the challenge of sustainability will profoundly affect the competitiveness and even the survival of organizations (Lubin & Esty, 2010). Despite these advances, sustainability research in the field of intellectual capital has not become a widely studied topic in premier journals. Additionally, practitioners and academics have become increasingly interested in this notion and how it relates to other concepts such as corporate reputation (Fombrun, 2005; Waddock, 2002). In part, this is due to the belief that elements of sustainability are key drivers of corporate reputation. These topics turn into an organizational outcome improvement, and this is the reason that makes it decisive to identify, manage and control the actions linked to sustainability and corporate reputation. Based on these ideas, in the literature review section, it will be presented three main research hypotheses that relate corporate sustainability dimensions to corporate reputation.

Thus, this paper mains to offer an understanding of the relationship between sustainability and corporate reputation according to the knowledge-based theory since the current academic literature does not have an understanding of how sustainability and corporate reputation interact. We divide the concept of sustainability into three main dimensions: economic, social and environmental. To our knowledge, in any case has been studied simultaneously the influence of sustainability dimensions on the corporate reputation, which is a knowledge gap in the academic literature regarding intellectual capital and the knowledge-based theory. Our findings show that the economic, social and environmental domains of sustainability have a direct and positive effect on corporate reputation.

We decided to conduct our research in the Spanish tourism industry, more specifically in the hospitality sector, for several reasons. First, it is a sector in which sustainable initiatives are developed (De Grosbois, 2012) and secondly, this research field helps us avoid the limitations of laboratory experiments, since data are obtained in real conditions of use. Finally, this paper is structured as follows. The next section presents the theoretical framework and reviews the literature on intellectual capital, relational capital, corporate reputation and sustainability. Section three presents the research methodology. The development of hypothesis is presented in the fourth section followed by the presentation of the results. Finally, concluding remarks and implications for management are presented.

Conceptual framework

Intellectual capital: The role of corporate reputation in developing relational capital

Recent years have been marked by the increasing importance of the role of intangible assets in firms (Hansen, Nohria & Tierney, 1999; Lev, 2001). Several authors declare that the current inclination for organizations is to focus more on intangible assets when seeking competitive advantages and less on material assets (Bontis, 1996; Martín de Castro et al., 2004) and that firms with an adequate intellectual capital have a better chance of survival (Hormiga et al., 2011). The concept of “intellectual capital” was popularized by Tom Stewart in 1991 when Fortune Magazine published his article “Brainpower: How intellectual capital is becoming America’s most valuable asset” (Bontis, 1996). In spite of the immense amount of research about this topic, there is still no single definition commonly accepted. In this paper intellectual capital is defined as “the knowledge that can be converted into future profits and comprises resources such as ideas, inventions, technologies, designs, processes and informatic programs” (Sullivan, 1999).

Several authors have recognized that economic wealth comes from knowledge assets or intellectual capital, and its practical application (Dean & Kretschmer, 2007). However, the emphasis on this concept is relatively new, and the management of the organization's intellectual capital has become one of the key tasks in the corporate agenda. Nevertheless, this labor is especially difficult because of the problems involved in the identification, classification, measurement and strategic evaluation of intellectual capital. In recent decades, various alternatives have been proposed for the categories that involve intellectual capital. One of the classifications with the greatest consensus among academics is the one based on three dimensions including human, structural and relational capital (Brennan & Connell, 2000; Roos, Bainbridge & Jacobsen, 2001; Marr & Roos, 2005). Among these three domains, relational capital is recognized by many authors as the organization's most important intangible resource by playing a fundamental role in firms. The dimension of relational capital is based on the notion that firms are considered not to be isolated systems but as systems that are, to a great extent, dependent on their relations with their environment (Martín de Castro et al., 2004). Thus, this type of capital includes the value generated by relationships not only with customers, but with suppliers, shareholders and stakeholders, both internal and external.

In this regard, the strategic role of corporate reputation in gaining competitive advantage and relational capital has strong support in the academic literature. Relevant authors such as Barney (1986), Dierickx and Cool (1989) or Grant (1991), highlight its importance. In this sense, Fombrun and Shanley (1990) sustain that a good reputation is important to obtain competitive advantage because provide relevant information to stakeholders about the firm. As previously mentioned, corporate reputation is understood as the “set of perceptions held by people inside and outside a company” (Fombrun, 1996). This notion, as the awareness or perception about corporate behavior by its stakeholders (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990; Fombrun, 1996), will influence relational processes with the agents of the closer environment. A firm’s reputation is produced by the interactions of the company with its stakeholders and by information about the company and its actions circulated among stakeholders (Fombrun, 1996). Thus, reputation has an important influence upon stakeholder beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors when these groups have incomplete information regarding organizational characteristics (Weigelt & Camerer, 1988). The foundation for the influence of reputation upon stakeholder behavior is derived from the game theory (Weigelt & Camerer, 1988) and signaling theory (Wernerfelt, 1988). The explanation to game theory models is that each agent has a set of privately known information that reflects their individual characteristics (Weigelt & Camerer, 1988). In organizations, this private information includes issues such as plant capacity, strategic preferences or the quality of products and services (Milgrom & Roberts, 1986). Therefore, these characteristics influence the preferences and future behaviors of stakeholders. With regard to this, Fombrun and Shanley (1990) suggest a number of potential signals that influence reputation with a range of stakeholders: (1) market signals such as market performance, market risk or dividend policy, (2) institutional signals as institutional ownership, social responsibility and sustainability, media visibility or firm size, (3) accounting signals such as accounting profitability and accounting risk and (4) strategy signals as differentiation or diversification position. The role of reputational signals is to reduce uncertainty as to whether explicit and implicit contractual claims will be fulfilled (Cornell & Shapiro, 1987). Therefore, reputation has the effect of increasing the attractiveness of an exchange relationship (Smith, 1992; Erdem & Swait, 1998). By modifying stakeholder perceptions of uncertainty regarding the outcomes of an exchange with the organization, reputation reduces the perceived risk of the exchange. Ceteris paribus, reduced perceived risks, increases the propensity of stakeholders to enter into an exchange with the firm (Hayton, 2005).

Sustainability dimensions in business

From a business point of view, sustainability connotes three dimensions: economic, social and environmental (Choi & Ng, 2011; Sheth, Sethia & Srinivas, 2011). In this research authors understand the notion of sustainability meaning “to meet the present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987). Sustainability is an approach firms are increasingly adopting to conduct business. However, results from several international studies show that this notion is being adopted slowly. According to a McKinsey Global Survey (2010), based on responses from nearly 2,000 executives, reports that despite its recognized importance, companies are not taking a proactive approach to managing sustainability. Among the three dimensions previously mentioned, environmental sustainability has received the most attention to date. This dimension refers to the maintenance of natural capital (Goodland, 1995). As Stern (1997) argues, environmental damage caused by consumption threatens human welfare and health. The main environmental concerns arising from rapid growth in consumption are two-fold: environmental degradation risks and eco-system resource constraints. Environmental risks are losses and harm such as biodiversity loss, deforestation and soil erosion due to climate change and pollution of water systems and land (Sheth et al., 2011). Eco-system constraints suggest that the earth cannot support unlimited growth in consumption (Speth, 2008). This orientation is limited when compared to more recent developments in the concern for the environment and to a broader orientation of sustainability having not only environmental aspects but also economic and social concerns (Choi & Ng, 2011; Sheth et al., 2011).

The economic dimension of sustainability refers to companies' ability to create value and enhance financial performance. With the enduring international economic and financial crisis, society is deeply concerned with economic sustainability due to fear of general job losses and financial risks to government and public programs (Choi & Ng, 2011). Several authors have tried to articulate the significance of the economic dimension of sustainability. Sheth et al. (2011) have identified two different aspects of the economic dimension. The first one is related to conventional financial performance such as cost reductions, and the second issue relates to economic interests of external stakeholders such as a broad-based improvement in economic well-being and standard of living. To finish, social dimension of sustainability describes the consideration of societal issues like tolerance toward others or equal rights (Goodland, 1995) and is concerned with the well-being of people and communities as a noneconomic form of wealth (Choi & Ng, 2011). This dimension of sustainability has probably become more apparent due to the increasing number of financial scandals as well as a great number of public expectations of companies to do more for social well-being (Mohr & Webb, 2005).

Sustainability and corporate reputation

By revealing sustainability initiatives, companies are able to facilitate the projection of a social image (Gray, Kouhy & Lavers, 1995) which will lead to increased corporate reputation and reduce reputational risks (Fombrum, Gardberg & Barnett, 2000; Bebbignton, Larrinaga-González & Moneva, 2008). Actually, the inclusion of social and environmental activities in the corporate agenda is a part of the conversation between organizations and their publics and it provides information on firms' activities that help educate, inform and change perceptions and expectations of these stakeholders (Adams & Larrinaga-González, 2007). Corporate reputation can be conceptualized as the “set of perceptions held by people inside and outside a company” (Fombrun, 1996). A company's reputation is the perceptions of its relevant stakeholders, such as customers, employees, owners, suppliers and strategic partners, society and community (ranging from both local to international, including current and future generations), government or non-governmental organizations, among others. An advanced corporate reputation acts as both an intangible asset and a source of strategic advantage increasing companies' long term ability to create value (Caves & Porter, 1977) since corporate reputation is composed of a company's unique set of skills in delivering both economic and non-economic benefits (Fombrum, 1996). Sustainability is increasingly seen as a determinant of corporate reputation since firms show externally that they are aware of the need of managing a wider range of social and environmental issues (Friedman & Miles, 2001). Furthermore, this concept is relied upon to enhance corporate reputation (Becker-Olsen, Cudmore & Hill, 2006; Pirsch, Gupta & Grau, 2007) and academic literature has recently suggested that companies may use sustainability as a way to manage their reputation risk (Bebbington et al., 2008).

Sustainability has been found to reduce public scrutiny, providing a license to operate in society and enhancing the latitude of public tolerance when things go wrong (Klein & Dawar, 2004). In this way, sustainability may act as a barrier permitting the company a certain degree of tolerance for error in what, through the responsibilities imposed by its reputation and the promises made in its marketing communications, audiences have come to expect (Pomering & Johnson, 2009). As previously mentioned, academics and practitioners attribute considerable power to corporate reputation built on sustainability aspects. General benefits attributed to sustainability include investment appeal, market share, business performance and organizational attractiveness, among others (Maignan, Ferrell & Hult, 1999; Luce, Barber & Hillman, 2001). Firms that act in a socially responsible manner and have a history of fulfilling their obligations to various stakeholders are creating reputational advantage (Miles & Covin, 2000).

The influence of sustainability on corporate reputation has been theoretically proposed but, as far as it is known, in any case has been analyzed the influence of sustainability dimensions on corporate reputation. The importance of knowing if such influence exists in practice and determining its magnitude is due to the fact that this effect would provide empirical support for the idea that sustainability is an important source of competitive advantage (Caves & Porter, 1977; Fombrun, 1996) generating multiple business benefits. Hence, and based on the previous literature review we propose:

-

H1: The economic dimension of sustainability has a positive direct effect on corporate reputation.

-

H2: The social dimension of sustainability has a positive direct effect on corporate reputation.

-

H3: The environmental dimension of sustainability has a positive direct effect on corporate reputation.

Methodology

Data collection and sample

Personal surveys of customers were conducted in Spain according to a structured questionnaire in order to test the hypotheses. To design the research sample, a non-probability sampling procedure was chosen (Trespalacios, Vázquez & Bello, 2005). Particularly, a convenience sample was used. To guarantee greater representation of the data, a multistage sampling by quotas was made by characterizing the population according to two criteria relevant to the research: the sex and the age of the respondents, which is included in the Census Bureau (2010). From the target sample of 400 questionnaires, 382 questionnaires were completed, 18 were discarded as incomplete. Hence, the final response rate was 95.5 %. Data were gathered during the month of April 2011 in the Autonomous Community of Cantabria (Spain). The final sample consists of 186 females (49%) and 196 males (51%); 38 under the age of 25 (10%); 74 between the ages of 25 and 34 (19.5%); 71 between the ages of 35 and 44 (18.5%); 76 between the ages of 45 and 54 (20%) and 123 over the age of 55 (32.1%).

Finally, we decided to conduct our research in the Spanish tourism industry, more specifically in the hospitality sector, for several reasons. First, it is a sector in which sustainable initiatives are developed (De Grosbois, 2012) and secondly, this research field helps us avoid the limitations of laboratory experiments, since data are obtained in real conditions of use. Table 1 displays the main characteristics of the research. Preliminary versions of the questionnaire were administered to a convenience sample of 18 consumers, and pretest results were used to improve measures and design and appropriate structure for the questionnaire. Existing well-established multiple-item 7-point Likert scales were adopted to measure our variables. Sustainability dimensions were measured using a seventeen-item scale from Martínez, Pérez and Rodríguez del Bosque (2012). To finish, we measured corporate reputation with four items developed by Ahearne, Jelinek and Rapp (2005). The final measures are provided in the Appendix.

|

Universe |

Hotel clients over 18 years of age |

|

Scope |

Spain (The Autonomous Community of Cantabria) |

|

Date of fieldwork |

April 2011 |

|

Sample |

382 valid questionnaires |

|

Sampling procedure |

Quota sampling according to the criteria of 1) sex and 2) age |

|

Processing of data |

PASW v. 18.0, EQS v. 6.1 |

Table 1. Research technical record

Psychometric properties of the measurement instrument

In order to achieve the objectives of our research, the authors followed Anderson and Gerbing (1988) two-stage procedure. First of all, the goodness of the measurement instrument's psychometric properties was analyzed by a confirmatory factor analysis and secondly, the structural relations among the theoretically proposed latent variables were analyzed through a structural equation model. Both the measurement model and the causal relations model were estimated using the maximum likelihood method with robust estimators using EQS v.6.1.

The psychometric properties (reliability and validity) of the measurement instruments were assessed by a confirmatory factor analysis containing all the multi-item constructs in our theoretical framework by using EQS v.6.1 (Bentler, 1995). The reliability of the measurement scales proposed was evaluated using the Cronbach's alpha coefficient and by an average variance extracted (AVE) (Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson, 2010). The values of these statistics exceed the minimum recommended values of 0.7 and 0.5, respectively (Hair et al., 2010), which confirm the internal reliability of the model. In addition, all the items are significant at a confident level of 95% and their standardized lambda coefficients exceed 0.5 (Steemkamp & Van Trijp, 1991), confirming the convergent validity of the model. Finally, in order to confirm the discriminant validity, the confidence intervals for the correlation of the constructs are estimated and compared with the unit. In none of the cases did the intervals contain the value 1. Therefore, the measurement model proposed is correct. Finally, the goodness of fit of the analysis was verified with the Satorra-Bentler c2 (S-B c2) (p < 0.05) and the comparative fit indices NFI, NNFI, IFC and IFI, which are the most common measures for confirmatory tests (Uriel & Aldás, 2005). All values were greater than 0.9 (Bentler, 1995), indicating that the model provides a good fit. Table 2 shows the statistics calculated to verify these properties and the main goodness of fit indicators.

|

Factor |

Item |

Std. lambda |

Cronbach's α |

AVE |

|

ECO |

ECO1 ECO2 ECO3 ECO4 |

0.816 0.883 0.788 0.849 |

0.902 0.697 |

|

|

SOC |

SOC1 SOC2 SOC3 SOC4 SOC5 SOC6 |

0.773 0.685 0.773 0.700 0.709 0.770 |

0.876 0.542 |

S-Bc2 441.82 (p=0,000) |

|

ENV |

ENV1 ENV2 ENV3 ENV4 ENV5 ENV6 ENV7 |

0.761 0.764 0.722 0.718 0.787 0.761 0.748 |

0.985 0.579 |

BBNFI=0.905 BBNNFI=0.931 CFI=0.941 IFI=0.941 RMSEA=0.061 |

|

REP |

REP1 REP2 REP3 REP4 |

0.891 0.898 0.780 0.900 |

0.925 0.755 |

|

Table 2. Confirmatory factor analysis of the final model

Analysis of structural relations and hypothesis testing

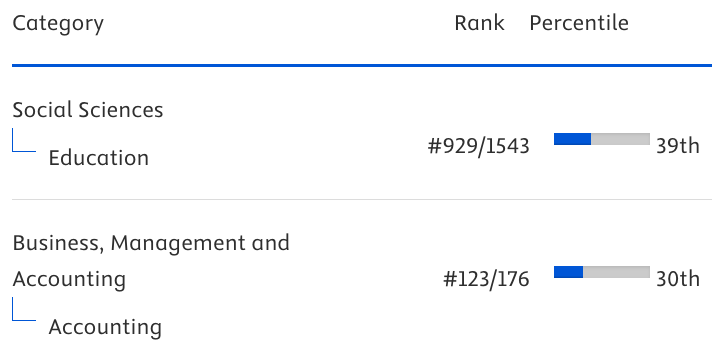

Table 3 and Figure 1 show the standardized coefficients for the structural relations tested. As it is shown, the goodness of fit indices for the structural model show a good fit so that it is possible to test the proposed hypotheses. H1, H2 and H3 are supported (β = 0.326*; β = 0.228*; β = 0.173*) as the economic, social and environmental dimension of sustainability have a positive direct effect on corporate reputation. This study shows that economic sustainability is considered to be the most important dimension to enhance corporate reputation (β = 0.326*; p < 0.05*), followed by social sustainability (β = 0.228*; p < 0.05*). These results give empirical support to the idea that the efforts made by companies towards sustainability will be rewarded by the projection of a positive reputation. Therefore, the proposed model is totally supported by the results.

Figure 1. Structural model estimation

|

Hypotheses |

Structural relationship |

Std. coefficient |

Contrast |

|

H1 |

Economic dimension ® Reputation |

0.326 (4.480)* |

Accepted |

|

H2 |

Social dimension ® Reputation |

0.228 (2.300)* |

Accepted |

|

H3 |

Environmental dimension ® Reputation |

0.173 (1.982)* |

Accepted |

|

|

BBNFI = 0.905 BBNNFI = 0.932 CFI = 0.942 S-Bc2 438.23 (p = 0,000) |

IFI = 0.942 |

|

|

p < 0.05* |

|

|

|

Table 3. Structural equation model results

Conclusions, limitations and future lines of research

The results of this study provide support for our argument that the dimensions of sustainability will positively influence corporate reputation as one of the main components of relational capital. The authors have developed a structural equation model to test the hypothesis. The three hypotheses suggest that economic, social and environmental domains of sustainability have a positive direct effect on corporate reputation. In this sense, it seems that the economic and social dimensions of sustainability present the greatest influence on this intangible asset. Such findings are relevant since they add several contributions to the existing academic literature.

Firstly, this study shows that economic sustainability is considered to be the most important dimension to enhance corporate reputation (β = 0.326*; p < 0.05*). Therefore, we could generalize that, in order to increase corporate reputation, it is necessary to understand the economic domain from a broader perspective and not only in terms of profit maximization. Thus, companies must reveal information to their stakeholders regarding issues such as obtaining the greatest possible profits, achieving long-term success, improving its economic performance and ensuring their survival and success in the long run. Secondly, social sustainability also encompasses a great influence on corporate reputation (β = 0.228*; p < 0.05*). Social initiatives such as helping to solve social problems, playing a role in society that goes beyond mere profit generation, actively collaborating in cultural and social events, or committing to improving the welfare of the communities in which companies operate, are actions that companies should devote resources to in order to strengthen reputation. This way, by providing relevant information to stakeholders about the firm regarding sustainability, companies will obtain a competitive advantage based on a good reputation.

This research improves our understanding of reputational capital, corporate reputation and sustainability. Given that limited empirical research addresses the nature and consequences of sustainability in the context of intellectual capital, this study provides a starting point for future work in this area. Our study makes theoretical distinctions between the key dimensions of sustainability and contributes to understanding their effect on a firm's reputation. Empirical support for the role that sustainability dimensions play in corporate reputation encourages both researchers and practitioners to examine the nature, antecedents and consequences of reputational capital.

The present study has a number of implications for practitioners. The most important implication for practitioners is that economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainability have a direct and positive impact on corporate reputation. This should give managers the argument they need to justify the costs that are associated with sustainable issues. Apart from that, this research allows managers to identify the activities in which companies can devote resources to in order to increase firm's reputation. By knowing these specific economic, social and environmental activities, companies can understand, analyze and make decisions in a better way about its sector and about the stakeholders that assess these initiatives. At present, it is not sufficient for managers to know the perceptions that consumers have about companies and the reputation arising from them, but it is also necessary to know the factors causing these perceptions and reputation, so that it is possible for managers to control these aspects efficiently and effectively. Additionally, these findings suggest that the areas of corporate reputation and sustainability are strongly interrelated, so it follows that these concepts could be managed in an integrated way. Companies are encouraged to explore how corporate sustainability and reputation activities could positively be managed jointly, since organizations may manage these concepts in separate business areas.

Finally, to refine the findings of this study, some limitations are outlined. First, relational capital involves several dimensions such as customer, shareholder or community relational processes (Martín de Castro et al., 2004) which have not been incorporated to this study. Thus, future studies may analyze the role of corporate reputation and sustainability in the formation and development of the different relationships that conform relational capital. Secondly, with the enduring international economic and financial crisis, society is deeply concerned with economic sustainability. The complicated economic environment currently experienced worldwide may affect the perceptions of Spanish consumers and their ratings. The crosscutting nature of this research inhibits an understanding of the variations in the perceptions of the customers surveyed over time, suggesting that this research could be expanded by a longitudinal study. Thirdly, the current study has been conducted with consumers of hotel companies in Spain and it is not clear in how far the findings can be generalized to other industries, stakeholders or countries. Future research could extend this research by including different stakeholders' expectations of corporate sustainability and reputation.

References

ADAMS, C.A; LARRINAGA-GONZÁLEZ, C. (2007). Engaging with organizations in pursuit of improved sustainability accounting performance. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 20(3): 333-355. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09513570710748535

AHEARNE, M.; JELINEK, R.; RAPP, A. (2005). Moving beyond the direct effect of SFA adoption on salesperson performance: Training and support as key moderating factors. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(4): 379-388. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.09.020

ANDERSON, J.C.; GERBING, D.W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3): 411-423. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

BARNEY, J.B. (1986). Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck, and business strategy. Management Science, 32(10): 1231-1241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.32.10.1231

BARNEY, J.B. (2001). Is the resource-based view a useful perspective for strategic research? Academy of Management Review, 26(1): 41-56.

BEBBIGNTON, J.; LARRINAGA-GONZÁLEZ, C.; MONEVA, J.M. (2008). Corporate social responsibility and reputation risk management. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 21(3): 337-362. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09513570810863932

BECKER-OLSEN, K.L.; CUDMORE, B.A.; HILL, R.P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1): 46-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.01.001

BENTLER, P.M. (1995). EQS structural equations program manual. Multivariate Software Encino, CA.

BONTIS, N. (1996). There is a price on your head: managing intellectual capital strategically. Business Quarterly, 60(4): 40-47.

BRENNAN, N.; CONNELL, B. (2000). Intellectual capital: Current issues and policy implications. In the 23rd Annual Congress of the European Accounting Association, Munich.

BUENO, E. (2000). Perspectivas sobre Dirección del Conocimiento y Capital Intelectual. I.U. Euroforum Escorial, Madrid.

CIC (2012). Model for the Measurement and Management of Intellectual Capital: “Intellectus Model”. Intellectus Documents, 9/10. Centro de Investigación de la Sociedad del Conocimiento (CIC), Madrid.

CAVES, R.E.; PORTER, M.E. (2007). From entry barriers to mobility barriers: Conjectural decisions and contrived deterrence to new competition. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 91: 241-262. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1885416

CENSUS BUREAU (2010). Available at: http://www.ine.es

CHEN, Y.S. (2008). The positive effect of green intellectual capital on competitive advantages of firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 77: 271-286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9349-1

CHEN, Y.S; LAI, S.B.; WEN, C.T. (2006). The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. Journal of Business Ethics, 67: 331-339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9025-5

CHOI, S.; NG, A. (2011). Environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability and price effects on consumer responses. Journal of Business Ethics, 104: 269-282. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0908-8

CORNELL, B.; SHAPIRO, A.C. (1987). Corporate stakeholders and corporate finance. Financial Management, 16: 5-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3665543

DEAN, A.; KRETSCHMER, M. (2007). Can ideas be capital? Factors of production in the postindustrial economy: A review and critique. Academy of Management Review, 32(2): 573-594. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.24351866

DE GROSBOIS, D. (2012). Corporate social responsibility reporting by the global hotel industry: Commitment, initiatives and performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3): 896-905. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.10.008

DIERICKX, I.; COOL, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science, 35(12): 1504-1513. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.12.1504

EDVINSSON, L.; MALONE, M.S. (1997). Intellectual capital. Realizing your company's true value by findings its hidden brainpower. Harper Collins Publishers: New York.

ERDEM, T.; SWAIT, J. (1998). Brand equity as a signaling phenomenon. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 7: 131-157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp0702_02

FIGGE, F.; HAHN, T. (2005). The cost of sustainability capital and the creation of sustainable value by companies. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 9: 47-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/108819805775247936

FOMBRUN, C.J. (1996). Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image. Harvard Business School Press: Harvard.

FOMBRUN, C.J. (2005). Building corporate reputation through CSR initiatives: Evolving standards. Corporate Reputation Review, 8(1): 7-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540235

FOMBRUN, C.J.; GARDBERG, N.A.; BARNETT, M.L. (2000). Opportunity platforms and safety nets: Corporate citizenship and reputational risk. Business and Society Review, 105(1): 85‑106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/0045-3609.00066

FOMBRUN, C.; SHANLEY, M. (1990). What's in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33(2): 233-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/256324

FRIEDMAN, A.L.; MILES, S. (2001). Socially responsible investment in corporate social and environmental reporting in the UK: An exploratory study. British Accounting Review, 33(4): 523-548. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/bare.2001.0172

GOODLAND, R (1995). The concept of environmental sustainability. Review of Ecology Systems, 26: 1-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.26.110195.000245

GRANT, R.M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3): 114-135. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/41166664

GRANT, R.M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17: 109-122.

GRAY, R.; KOUHY, R.; LAVERS, S. (1995). Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability, 8(2): 47-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09513579510146996

HAIR, J.F.; BLACK, W.C.; BABIN, B.J.; ANDERSON, R.E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. Pearson Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River.

HANSEN, M.T.; NOHRIA, N.; TIERNEY, T. (1999). What's for managing knowledge?. Harvard Business Review, 77(2): 106-116.

HAYTON, J.C. (2005). Promoting corporate entrepreneurship through human resource management practices: A review of empirical research. Human Resource Management Review, 15: 21-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2005.01.003

HORMIGA, E.; BATISTA, R.; SÁNCHEZ, A. (2011). The role of intellectual capital in the success of new ventures. International Entrepreneurship Management Journal, 7(1): 71-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11365-010-0139-y

KLEIN, J.; DAWAR, N. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and consumers' attributions. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21: 203-217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2003.12.003

LEV, B. (2001). Intangibles management, measurement and reporting. The Brookings Institution: Washington.

LUBIN, D.A.; ESTY, D.C. (2010). The Sustainability Imperative. Harvard Business Review, 88(5): 42-50.

LUCE, R.A.; BARBER, A.E.; HILLMAN, A.J. (2001). Good deeds and misdeeds: A mediated model of the effect of corporate social performance on organizational attractiveness. Business Society, 40(4): 397-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000765030104000403

MAIGNAN, I.; FERRELL, O.C.; HULT, G.T.M. (1999). Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and business benefits. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(4): 455-469. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0092070399274005

MARR, B.; ROOS, G. (2005). A Strategy perspective on intellectual capital. In B. Marr (Ed.), Perspective on intellectual capital. Multidisciplinary insights into management, measurement and reporting. Elsevier: Boston. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-7799-8.50007-3

MARTÍN DE CASTRO, G.; LÓPEZ, P.; NAVAS, E. (2004). The role of corporate reputation in developing relational capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 5(4):575 585. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14691930410567022

MARTÍNEZ, P.; PÉREZ, A.; RODRÍGUEZ DEL BOSQUE, I. (2012). Developing a scale for measuring corporate social responsibility in tourism. In Marketing to citizens: Going beyond customers and consumers of the 41st EMAC Annual Conference, Lisbon.

MCKINSEY GLOBAL SURVEY (2010). How companies manage sustainability. Available at:

MILES, M.P.; COVIN, J.G. (2000). Environmental marketing: A source of reputational, competitive, and financial advantage. Journal of Business Ethics, 23(3): 299-311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1006214509281

MILGROM, P.; ROBERTS, J. (1986). Relying on information of interested parties. Rand Journal of Economics, 17: 18-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2555625

MOHR, L.A.; WEBB, D.J. (2005). The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39(1): 121-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2005.00006.x

PIRSCH, J.; GUPTA, S.; GRAU, S.L. (2007). A framework for understanding corporate social responsibility programs as a continuum: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Ethics, 70(2): 125-140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9100-y

POMERING, A.; JOHNSON, L. (2009). Constructing a corporate social responsibility reputation using corporate image advertising. Australasian Marketing Journal, 17(2): 106-114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2009.05.006

ROOS, G.; BAINBRIDGE, A.; JACOBSEN, K. (2001). Intellectual capital as a strategic tool. Strategic & Leadership, 29(4): 21-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10878570110400116

SHETH, J.N.; SETHIA, N.K.; SRINIVAS, S. (2011). Mindful consumption: A customer-centric approach to sustainability. Journal of the Academy Marketing Science, 39(1): 21-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0216-3

SPENDER, J.C. (1996). Making knowledge the basis of a dynamic theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17: 45-62.

SMITH, P.J. (1992). How to present your firm to the world. Journal of Business Strategy, January-February: 32-36.

SPETH, J.G. (2008). The bridge at the edge of the world. Yale University Press: New Haven.

STEENKAMP, J.B.; VAN TRIJP, H.C.M. (1991). The use of LISREL in validating marketing constructs. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 8(4): 283-299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-8116(91)90027-5

STERN, D.A. (1997). The capital theory approach to sustainability: A critical appraisal. Journal of Economic Issues, 31(1): 145-173.

SULLIVAN, P.H. (1999). Profiting from intellectual capital. Journal of Knowledge Management, 3(2): 132-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13673279910275585

TRESPALACIOS, J.A.; VÁZQUEZ, R.; BELLO, L. (2005). Investigación de Mercados. Thomson: Madrid.

URIEL, E.; ALDÁS, J. (2005). Análisis multivariado aplicado. Thomson: Madrid.

WADDOCK, S. (2002). Leading Corporate Citizens. Vision, Values, Value Added. McGraw-Hill: Boston.

WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development) (1987). From one earth to one world: An overview. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

WEIGELT, K.; CAMERER, C. (1988). Reputation and corporate strategy: A review of recent theory and applications. Strategic Management Journal, 9: 443-454. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250090505

WERNERFELT, B. (1988). Umbrella branding as a signal of new product quality. Rand Journal of Economics, 19: 458-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2555667

Appendix

|

Ident. |

Item |

|

I think this company… |

|

|

Economic dimension |

|

|

ECO1 |

Obtains the greatest possible profits |

|

ECO2 |

Tries to achieve long-term success |

|

ECO3 |

Improves its economic performance |

|

ECO4 |

Ensures its survival and success in the long run |

|

Social dimension |

|

|

SOC1 |

Is committed to improving the welfare of the communities in which it operates |

|

SOC2 |

Actively participates in social and cultural events |

|

SOC3 |

Plays a role in society that goes beyond mere profit generation |

|

SOC4 |

Provides a fair treatment of employees |

|

SOC5 |

Provides training and promotion opportunities to their employees |

|

SOC6 |

Helps to solve social problems |

|

Environmental dimension |

|

|

ENV1 |

Protects the environment |

|

ENV2 |

Reduces its consumption of natural resources |

|

ENV3 |

Recycles |

|

ENV4 |

Communicates to its customers its environmental practices |

|

ENV5 |

Exploits renewable energy in a productive process compatible with the environment |

|

ENV6 |

Conducts annual environmental audits |

|

ENV7 |

Participates in environmental certifications |

|

Corporate reputation |

|

|

REP1 |

I consider that X is a respected company |

|

REP2 |

I consider that X is a recognized company |

|

REP3 |

I consider that X is an admired company |

|

REP4 |

I consider that X is a prestigious company |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Intangible Capital, 2004-2025

Online ISSN: 1697-9818; Print ISSN: 2014-3214; DL: B-33375-2004

Publisher: OmniaScience